What is a Simulated Universe?

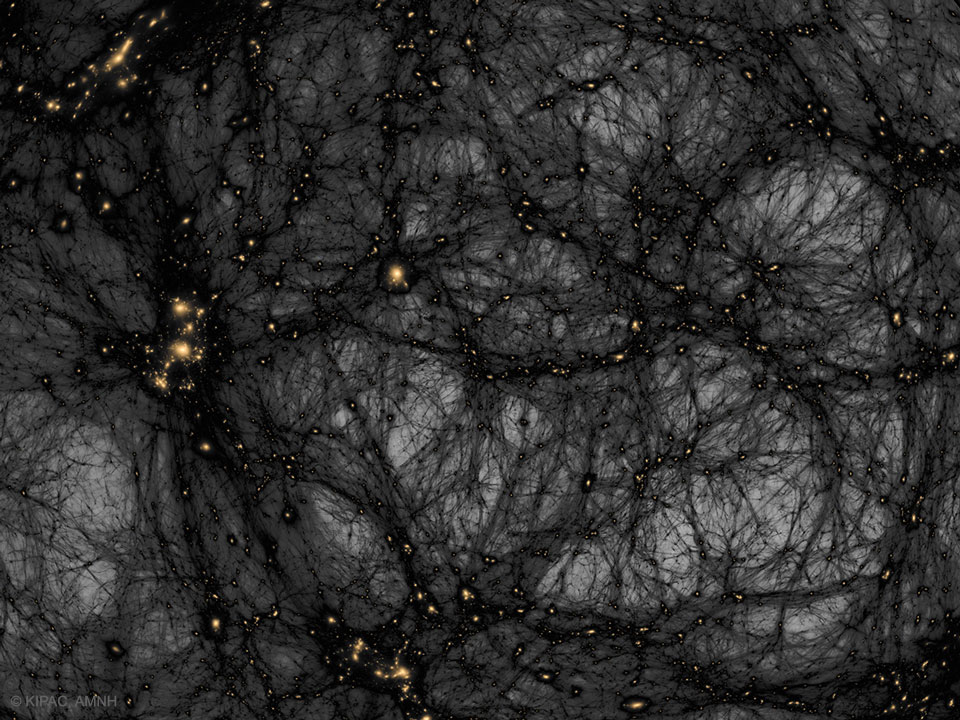

The Simulated Universe argument suggests that the universe we inhabit is an elaborate emulation of the real universe. Everything, including people, animals, plants, and bacteria are part of the simulation. This also extends further than Earth. The argument suggests that all the planets, asteroids, comets, stars, galaxies, black holes, and nebula are also part of the simulation. In fact the entire Universe is a simulation running inside an extremely advanced computer system designed by a super intelligent species that live in a parent universe.

In this article, I provide an exposition of the Simulated Universe argument and explain why some philosophers believe that there is a high possibility that we exist in a simulation. I will then discuss the type of evidence that we would need to determine whether we exist in a simulation. Finally, I will describe two objections to the argument before concluding that while interesting, we should reject the Simulated Universe argument.

The Possibility

The possibility that we exist in a simulated universe is derived from the idea that it is possible for a computer to simulate anything that behaves like a computer. A computer can run a simulation of any mechanistic system that follows a pre-defined series of rules. Now, because the Universe is a rule following system that operates according to a finite set of physical laws that we can understand, it follows that it can be simulated by a computer.

The proponents of the Simulated Universe argument suggest that if it is possible for us to simulate a universe, then it is likely that we actually exist inside a simulated universe. Why do they have this belief? Well, proponents of the Simulated Universe argument suppose that if it is possible for us to build such a simulation, then we will probably do so at some time in the future, assuming that our human desires and sensibilities remain much the same as they are now (Bostrom 2001:pg 9). They then reason that any species that evolves within the simulation will probably build their own Simulated Universe. We know that it is possible for them to do so, because they exist, and they are inside a simulated universe. It is possible to continue this nesting of universes indefinitely, each universe spawning intelligent species that build their own simulations. Now, given the near infinite number of child universes, it is more likely that we exist in one of the billions of simulations rather than the one parent universe. This becomes especially apparent when we consider the possibility that within these universes there may be many worlds with intelligent life, all creating their own simulations.

So how does this all work? Well, when you look at a computer running a simulated universe it is not the case that you can switch on a video screen or computer monitor to peak inside the universe. The computer does not contain virtual reality creations of people living out their lives in their world. It is not like playing a videogame such as “The Sims” or “Second Life”. There are no graphics involved. From the outside looking in, all you see are numbers. That’s all it is. Complicated manipulation of numbers. As with all software, these numbers are instantiated through the computer hardware. They are stored on permanent storage devices such as Hard-drives, and they are moved into RAM to be operated upon by the Central Processing Units (CPUs). The numbers in a simulated universe program represent the laws of physics in the universe. They also represent matter and energy in the universe. As the program runs, the numbers are manipulated by the program rules–the algorithms representing the laws of physics. This manipulation yields different numbers which continue to be operated on by the program rules. Large data structures of numbers are moved around within the computer’s memory as they interact with other data structures. As the simulated universe grows, these structures become increasingly complex but the laws that govern their behavior remains constant and unchanged.

So, from the designer’s point of view the simulated universe contains nothing other than complicated data structures. But for the creatures that exist inside the simulated universe it is all real. They look out of their windows and marvel at beautiful sunsets. They walk around outside and enjoy the smell of freshly cut grass. They may study the stars in their sky and dream about one day visiting other worlds. For the inhabitants of the simulated universe everything is solid and tangible. But just like the real universe, it is all reducible to numbers and rules.

It is important to note that the computer is not simulating every subatomic particle in the universe. In his 2001 article, Nick Bostrom points out that it would be infeasible to run a simulation down to that level of detail. He suggests that the simulation need only simulate local phenomena to a high level of detail. Distant objects such as galaxies can have compressed representations because we do not see them in enough detail to distinguish individual atoms (Bostrom 2001:pg 4).

This is a point that we can take further. Perhaps the entire universe, including local phenomena, is compressed in some way. The simulation could be “interpreted” by its inhabitants as being made from individual atoms and subatomic particles, while in reality it is completely different. If we look at modern physics, we see that this is a reasonable possibility. Consider the indeterminacy principle in quantum physics. An observer cannot measure the position and momentum of a particle simultaneously. Furthermore, it seems that subatomic particles have no definite position or momentum until an observation is made. This is because subatomic particles do not exist in the sense we are used to experiencing on the macro level. Given the fact that we do not directly see subatomic particles we can conclude that their existence is an interpretation of a reality of which we have no direct access. In a simulated universe, this reality could take the form of data arrays which represent matter and energy.

The Original Simulated Universe

The Simulated Universe argument is not new. Frank Tipler put forward the idea of a Simulated Universe in his 1994 book The Physics of Immortality. He suggests that we may all become immortal when we are recreated inside a simulation of the universe at some time in the distant future. Tipler argues that at some point in the future, humans (or some other advanced species) will develop the technological ability to simulate the universe. Humans that reach such a point in evolution will, according to Tipler, have an extremely advanced sense of morality. They will recognize a moral problem with the notion of intelligent conscious beings living their lives and then dying. So to correct this moral problem they will recreate everyone that came before and let them live an immortal life inside a simulated reality.

There are problems with this view. The first, and most obvious, problem relates to the moral dilemma that these super advanced humans finds themselves in. Why do we assume that there is a moral problem with people dying and no longer existing. Sure, from our perspective it seems wrong, but from the perspective of humans with a super-evolved moral sense it may be more problematic to recreate us.

The second problem with Tipler’s idea is one of implementation. In order to recreate humans that once existed, future humans would require knowledge of each human being’s unique properties. This includes their personality, their memories, and the structure of their brains. It is unlikely that future humans will be able to gather this sort of information. The best they could do would be to create a new universe from scratch, switch it on and hope for the best. Their simulation will unfold according to the preset collection of rules that they built into it. After time, their universe will evolve and planets may form within it. Life could evolve on those planets and one day become intelligent enough to build its own computer simulations of the universe.

How would we know?

If a simulated universe provides a perfect replication of the real universe, then how could we ever know that we exist in a simulation. One way to find out would be to appeal to statistical probability. As stated earlier, if we accept the possibility that advanced beings can create a simulated universe, then it is highly likely that we actually exist in a simulation. The reason for this is that there will be billions of simulations but just one original universe. So it statistically there is a higher chance that we exist in a simulation than the original universe.

Another way to determine whether we exist in the original universe or a simulation would be to look for clues, or hints that this is not a real universe. Such clues may come in the form of imperfections in the simulation. Now, it is unlikely that we would find an obvious imperfection such as a fuzzy border on the other side of a mountain, which has never before been observed. Imperfections in the simulated universe would be subtle and almost undetectable. They will be found in the laws of physics.

In 2001, physicists Paul Davies and John Webb published a discovery that has been interpreted by some as such an imperfection. Their discovery came from observations of distant astronomical structures known as quasars. Now, because information from distant objects travels to us at the speed of light, looking at quasars effectively means looking back in time. Davies and Webb observed quasars as they were billions of years ago and discovered what could be interpreted as a change in the speed of light. They observed a change in the so-called Fine Structure Constant. This is a ratio involving the speed of light, the charge on the electron, and Planck’s constant (a unit involved in quantum physics). Webb admits that they cannot definitely say which aspect of the constant changed, but it could be the speed of light.

Regardless of which aspect of the Fine Structure Constant has changed, the discovery is significant. This is because constants are universal and unchangeable. They are built into the laws of physics. They are the same everywhere in the universe. These are fundamental laws of physics and therefore evidence of a shift (or glitch) in any of these constants could be used as evidence that we live in a simulated universe.

There are, of course, other explanations for the Davies/Webb observations. Theorists believe that the speed of light has been dropping since the beginning of the universe, and that it was once 10^60 times its current speed. It is possible that this reduction in speed is caused by a cosmos-wide change in the structure of the vacuum (Setterfield 2002). Perhaps the space/time continuum is stretching in some way. Or perhaps the gaps between superstrings is increasing. There are many possibilities, but the point I am making is that this type of observation is what we should look for as evidence that we live in a simulated universe.

Problems

The Simulated Universe argument relies on the assumption that future humans, or some advanced species, will have similar desires and sensibilities as current humans and will therefore want to create a simulated universe. In this section I will outline problems with this assumption. I will then suggest that the Simulated Universe argument should be rejected because it unnecessarily clutters our ontology.

1. The problem of morality

The first problem with the simulated universe argument is related to the point made above in regards to Tipler’s theory of immortality. I suggested that future humans may not feel a moral obligation to recreate humans. This is the thought that I would like to elaborate upon.

Given our current human desires and sensibilities, it seems that if we could develop sufficient computing power then we would create a simulated universe. Now the whole Simulated Universe Argument rests on this assumption. The idea is that if we can create a universe, then we will. And if this is true, then it is likely that we exist inside a simulation. But we need to ask the question: would a super advanced species with sufficient computing capacity actually create a simulated universe? If we accept for the moment that it will be possible for a future species to do such a thing, we need to decide if a species would do such a thing. Would it be the morally right thing to create a simulated universe? We can be very quick to state that it would definitely be the right thing to do, but that is from our current perspective. We are not yet advanced enough to create a simulated universe.

Bostrom believes that an advanced civilization will choose to create a simulated universe. He suggests that humanity’s existence is viewed as being of high ethical value. If this is true, then the world would be a better place if an advanced civilization created a universe containing creatures like us (Bostrom 2001:pg 9).

But morality, like all cultural phenomena, evolves. It is a conceit to assume that our current state of moral reasoning will remain unchanged. Highly advanced civilizations may find it morally abhorrent to create a universe and populate it with living beings. Consider life on Earth. We live on a planet full of creatures that have to destroy each other to survive. Humans, who have arguably the highest level of intelligence on Earth, kill animals, pollute the environment, torture children, tell lies, commit crimes, and kill each other for greed. Would an advanced species think it is a good thing to create another universe that could possibly contain this level of pain and suffering? Its possible that a future species would choose not to create a simulated universe because doing so would increase pain and suffering in the world.

The assumption that an advanced species will want to create a simulated universe relies too heavily on the idea that they will share our moral standards. We cannot make such an assumption, so the likelihood that we exist in a simulated universe may be a great deal lower than originally thought. I am not saying that it is impossible. All I am suggesting is that more thought needs to be put into the look of future moral reasoning before we can rest the Simulated Universe Argument on this assumption.

2. Are we replacing God with a Godlike species?

Another problem with the Simulated Universe argument is that suffers from similar problems to arguments for the existence of God–specifically The Cosmological argument.

Traditionally, the Cosmological argument attempts to solve the problem of where the universe came from by stating that:

1. Everything that exists has a cause,

2. The universe exists,

3. Therefore, the universe was caused,

4. The name of the cause of the universe is God,

5. Therefore God exists.

Now, the standard objection to this argument runs as follows:

If everything has a cause, then God also has a cause. The cause of God must be something equally God-like. Therefore, there must be more than one God, and this does not fit the standard religious view.

Supporters of the Cosmological argument then complain that there cannot be more than one God, and the the God who created the universe is either uncaused, self-caused, or existed forever before the universe.

But here they run into difficulty. As soon as they allow that at least one thing can be either uncaused, self-caused, or existed forever then they open the possibility that the universe could be uncaused, self-caused, or existed forever. And since we favor economy in our ontology, it is more rational to conclude that there is no reason to invoke the existence of God to explain the universe.

The Simulated Universe argument seems to suffer from the same problem. By allowing for the possibility that we exist in a simulation, we open up the possibility of an infinite number of parent universes. Supporters of the Simulated Universe argument may state that there is an ultimate parent universe, which was caused by a Big Bang or some similar event. Or they may claim that the parent universe existed forever. But these responses are the same as responses from supporters of the Cosmological argument. They too suggest that there is an ultimate God, and it all stops there. I am suggesting that if this is unsatisfactory for the Cosmological argument, then it should be unsatisfactory for the Simulated Universe argument.

Supporters of the Simulated Universe argument may complain here, and state that there is a fundamental difference between their view and the Cosmological argument. They may suggest that their argument is different because it is based on the existence of real creatures that have a biology and use technology, while the Cosmological argument is based on a supernatural God. But I am not sure the there is a difference. From our perspective there is no difference between a supernatural God and a super intelligent species from another universe. Both entities are equally difficult to describe. We can never know the nature of a parent universe. We cannot know about how their biology works because we are unable to visit and have a look. Creatures in the parent universe are unknowable, and from our perspective they are all-powerful.

For reasons of Ontological economy I believe we must reject the Simulated Universe argument. It creates a cluttered world-view. Why suppose that there exists an virtual infinity of parent-child universes when we can simply assume that there is one universe.

Conclusion

The possibility that we exist in a simulated universe is based on the assumption that if it is possible for us to create such a simulation, then one day we will do so. I have questioned this on the basis that it assumes a future morality that resembles our current morality. The mere possibility that we can create a simulated universe does not mean that we will create a simulated universe. This is because our future moral standards may lead us to view such a creation as a highly immoral act.

In addition to questioning the likelihood that we will one day create a simulated universe, I have also questioned the argument on the basis that it is a variation of the cosmological argument. It suffers from the same problems. Accepting the possibility that we exist in a simulation allows for a virtual infinity of parent universes. It doesn’t answer any questions about the origin of the universe; it just shifts the problem. Furthermore, it clutters our world view by introducing a multitude of universes when just one is required.

The Simulated Universe argument is an interesting thought experiment, but I believe we should reject the possibility that we exist in a simulation and focus on discovering the origin of this, the actual universe.

References

Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 15 August 2001 Lateline. Interview with John Webb, Interviewed by Tony Jones

http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/stories/s347215.htm, accessed August 2007.

Bostrom, Nick. (2003). “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?” inPhilosophical Quarterly (2003), Vol. 53, No. 211, pp. 243-255.

Davies, Paul. (2004). “Multiverse Cosmological Models” in Modern Physics Letter, Vol. 19, No. 10, pp. 727-743.

Tipler, Frank. (1994). The Physics of Immortality, Macmillan 1995.

Setterfield, Barry. (2002). Recent Lightspeed Publicity.

http://www.ldolphin.org/recentlight.html, accessed July 2007.